Blog

Chasing The Vanishing Face Of The Earth *

19 November 2025 Wed

DR. KUMRU EREN

Manager of Borusan Contemporary

*This article was originally published in the exhibition catalogue Edward Burtynsky: Shifting Topography.

“It seems that in the new planetary order that is gaining form two things, apparently unrelated to each other, are destined to be completely removed: the face and death,” noted Giorgio Agamben in a text penned during the pandemic. 1 The conceptual space he opened between these two seemingly unrelated things also pointed to the “cycle of tradition,” shattered by the excessive catastrophes of the contemporary world, and to the void left behind by the withdrawal of the idea of the future, situating the notion of mundus precisely within this emptiness. 2

In ancient Rome, the deceased would rejoin the world of the living through imago—wax death masks, molded and painted to resemble the face—preserved in the atriums of family homes. According to Polybius, following the funeral rites, the imago of the deceased was enshrined in a wooden box and displayed in the most visible part of the household. This wax face bore a complete resemblance to the original in both form and color. Agamben explains that these images were “not only the subject of a private memory, but were the tangible sign of the alliance and solidarity between the living and the dead, between past and present, which was an integral part of the life of the city.” 3 Just like a photograph in which the past and the future manifest simultaneously.

Legend has it that when Romulus founded Rome, he dug a pit he named mundus, the “world,” into which he and his companions threw a handful of earth from the lands they had come from. The pit was opened three times annually, and on those days, the mani—spirits of the dead—were believed to enter the city and share the presence of the living. “The world is nothing but the threshold through which the living and the dead, the past and the present, communicate,” says Agamben. 4

The Roman death mask, imago—the origin of the word image—as a representation of the human face, reflects this ancient Roman tradition of preserving presence through the image, which in turn evokes the manifestation of meaning within the image itself.

We need to remember that it is not only humans who have a face, but the earth does as well. The submergence of Halfeti and Hasankeyf, two of the earth’s primordial civilizations, felt like the erasure of this face—the very face of the land. “The face stolen by the submerged barriers was revived through a new encounter, resembling a death mask—the imago of absent ancestors—and became the face of the image.” Much like the wax masks of the Romans, it could only truly enter the realm of the living through its very image. The word “surface” is also linked to the face; it is the part that separated an object from space and gave it its face. 5

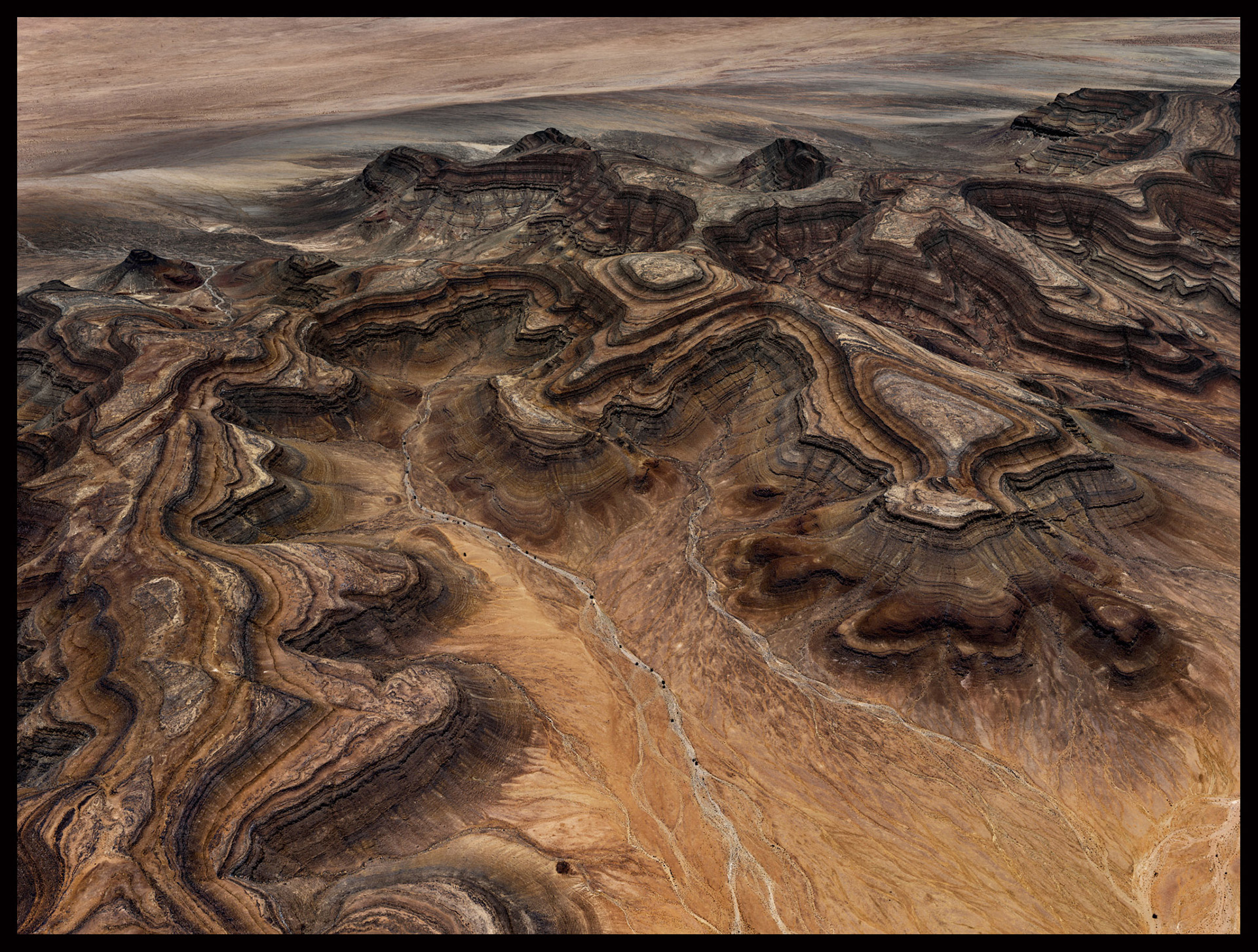

Throughout his over forty-year career in photography, Edward Burtynsky has chased the imago of this face—the one deeply scarred, altered, and sometimes erased by human activity. The artist documents moments when the faces or images of the living are lost and life and death are reduced to numbers and data, capturing the powerful marks left on that face as humanity transforms and shapes nature in the process of civilization’s growth. Spanning the expansive terrain from Africa to the Anatolian Plateaus, he reveals a portrait of the world shaped not only by mineral deposits and petroleum extracted from the earth but also ancient human activities on the soil, like agriculture—masterfully depicted through his use of large-format framing.

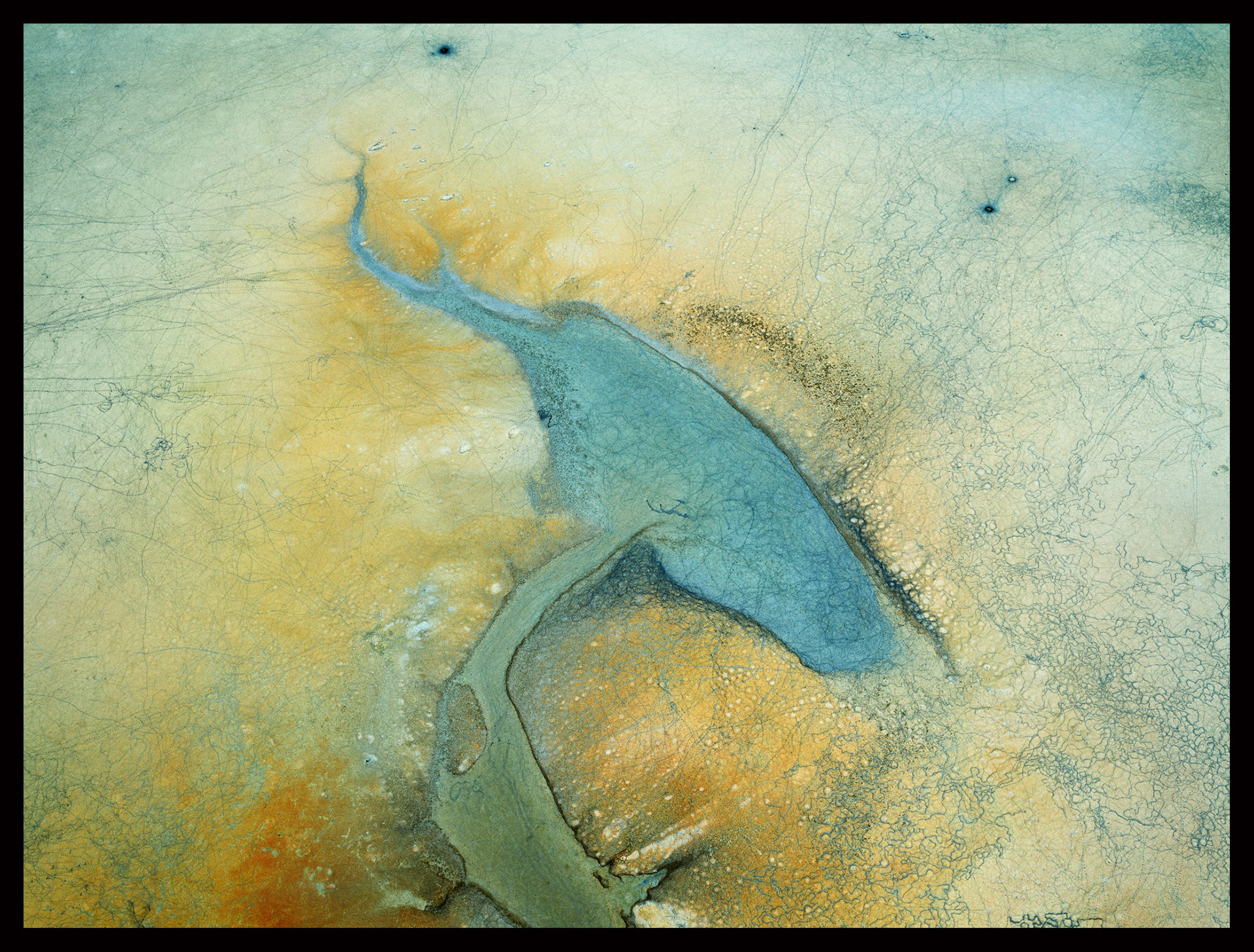

Edward Burtynsky, Salt Lakes #6, Bird Tracks, Lake Yarışlı, Burdur, Türkiye, 2022.

© Edward Burtynsky, Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, İstanbul

The exhibition Shifting Topography, born out of the artist’s long-term collaboration with the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, not only opens up vast intellectual terrain but also, through its documentary nature, captures both the soil’s power of self-transformation and the impact of human intervention—primarily focusing on the geography of Türkiye. Invited by Borusan in 2022, Burtynsky conducted a series of photographic expeditions across Türkiye, capturing various images at seven distinct locations—Konya, Burdur, Karaman, Ankara, Kırşehir, Aksaray, and Kayseri—at altitudes ranging from 125 to 500 meters, following a route established with the support of TEMA [The Turkish Foundation for Combating Soil Erosion, for Reforestation and the Protection of Natural Habitats]. The Erosion Project concurrently highlights both the marks that millennia of soil-dependent life have left on the land and the numerous human interventions aimed at controlling nature. Oscillating between documentation and composition, between factual record and abstraction, these photographs condense the three-dimensional landscape—described by the artist as one that can be abstracted without a horizon—into a two-dimensional form. In a sense, it crystallizes the past and future of the earth at an ambiguous point in time, presenting the world before us much like Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion map, merging it all into one image.

This act of bringing into view simultaneously opens up a discussion on today’s shifting paradigms of perspective: our ways of perceiving the world as humans parallel how we engage with it, while also holding an authoritative tone from a distant vantage point. The trajectory of Western art history from the horizon line and linear perspective to the elevated viewpoints rich with vanishing points, and more recently to today’s vertical perspectives—can be read within this framework. This digital gaze—capable of observing everywhere from above, like Google Earth—inevitably calls forth the concept of ground, as the disappearance of the Earth produces a constant sensation of falling, unlike the stability offered by flat or linear perspective. 6

Acknowledging that the concept of ground is fundamentally important for constructing an artistic gaze, Fırat Arapoğlu argues that “in order to develop an experimental and innovative perspective, it is necessary to reject the notion of an a priori constructed, given, and static ground.” He remarks that the greatest power of art lies in its ability to create a transient and groundless moment within a specific process. In this context, satellite images and drone technologies have brought forth a perspective “that relies not on a fixed, single vanishing point, but on multiple, inconsistent vanishing points.” 7

Arapoğlu states that linear perspective “mathematically flattens space by calculating an infinite, continuous, and homogeneous space, proclaiming it as a truth.” This constructed illusion contributes to the conceptualization of time as a linear phenomenon. The advancement of aerial photography has unfolded a new paradigm across a broad spectrum, ranging from science and culture to entertainment and the military. Today, three-dimensional technology, prevalent in areas from computer gaming to cinema and cultural sectors, has generated a vertical, rather than linear framework that influences social space as well. Unmanned aerial vehicles, observation satellites, and drone footage are the realities of this new era. 8

Edward Burtynsky, Tsaus Mountains #1, Sperrgebiet, Namibia, 2018.

© Edward Burtynsky, Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, İstanbul

Barbara Bolt examines Martin Heidegger’s conceptualization of the modern era, articulated in his 1950 essay “The Age of the World Picture,” which he characterizes as an epoch defined by depiction and/or envisagement. According to Heidegger, in the Western era extending from René Descartes to the present, the world has been reduced to a picture, that is, a representation. He argues that the world, as positioned outside oneself, before oneself, and in relation to oneself, has become nothing more than a picture. Heidegger’s point refers not so much to the production of a copy or image, but rather to a regime, system, norm, or model aimed at governing the world. In this context, the world is conceptualized as a picture. According to Heidegger, Descartes initiated this paradigm; his mathematization of knowledge laid the groundwork for reducing the world to a template. Thus, through the ability to envision, humans began to construct reality. 9 Undoubtedly, perspective holds a crucial role in the formation of this way of seeing. Situated in the continuum of visual paradigms extending from Alberti’s conceptualization of space, through Descartes’ subjectivity, to the current regimes of vertical perspective, depiction, and envisioning, the world is reconfigured—extending beyond Heidegger’s questioning of the Being of beings—into a surface/ground. As seen in Halfeti and Hasankeyf, the face of the earth could enter the realm of the living only through its image.

Just as the pit Romulus dug when founding Rome—the Earth—stands as a liminal threshold where the living and the dead, past and present, engage in dialogue, these images that reside on the marginal level of surface/ground similarly serve as “reflective pools” illuminating the intertwined constructs of time, community, identity, and culture and weaving together aesthetics and ethics to hold a compelling mirror to the age we inhabit. 10 Through his vertically framed landscapes that verge on the abstract, Burtynsky casts a critical gaze upon humanity’s way of seeing the world—as an image to be claimed—revealing its authoritarian, extractive, and elevated stance.

Burtynsky’s photographs are each an imago of the world—an aesthetic alliance between past and present, revealing how Being and nonbeing, life and death, memory and temporality are inevitably inscribed upon the face of the earth.

2- Jalal Toufic, The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster, Forthcoming Books, 2009, quoted in Zeynep Sayın, Çizginin Boşluğu [The Void of the Line], İstanbul: Norgunk Publishing, 2024, p. 45

3- Agamben, op. cit.

4- Agamben, ibid.

5- Sayın, op. cit., pp. 52–56

6- Sayın, ibid., p. 40

7- Fırat Arapoğlu, “Changing Perspective / Değişen Perspektif,” Current Debates in Social Science, vol. 30, London: IJOPEC Publication Limited, 2019, p. 52

8- Arapoğlu, ibid., pp. 53–55

9- Martin Heidegger, “Die Zeit des Weltbildes,” Holzwege, Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann, 1950, quoted in Barbara Bolt, Heidegger Reframed: Interpreting Key Thinkers for the Arts, London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, pp. 62–64

10- Edward Burtynsky, “Exploring the Residual Landscape,” https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/about/statement (Accessed July 30, 2025)

ABOUT THE WRITER

Kumru Eren, D.A., has provided consultancy for both national and international collections and institutions, with a particular focus on cultural heritage development, as well as collection and asset management. She received her Doctor of Arts degree with a dissertation on the phenomenon of “Globalization of Contemporary Art in Turkey,” framed through Jean-Luc Nancy’s theories. She has given lectures on critical art theories at Marmara University in İstanbul. Her articles, critiques, and reviews have appeared in exhibition catalogues, artist monographs and cultural publications including Istanbul Art News, Artam, Varlık, Hürriyet Kitap Sanat, and Hürriyet Seyahat. She currently serves as the Artistic and Executive Director of Borusan Contemporary and is a member of AICA Türkiye (International Association of Art Critics – Türkiye), Friends of Ulay Foundation, IACCCA (International Association of Corporate Collections of Contemporary Art), the Baksı Culture and Arts Foundation, the Baksı Platform, and the TOBB Creative Industries Council.