Blog

Pulse, Reflection, Repetition: Musical Perception in Doug Aitken’s Naked City

30 May 2025 Fri

Before I entered the Haunted Mansion, I went to stand by the Bosphorus. I was a little early, and this is a favorite place of mine both as a runner and as a composer. The urban soundscape of this position opposite the museum has its own sound signature—a dynamic layering of multiple sounds interwoven in time and space. The soundscape of Istanbul has often found its way into my composition practice, both as inspiration and as verbatim.

As a composer, I engage in the practice of deep listening, begun by Pauline Oliveros, which reimagines listening as an art form. You close your eyes and open your ears to all of the sounds available, equal parts meditation and musical practice. In Sonic Meditations: A Composer’s Practice (2005), Oliveros provides text-based "attention strategies" to focus the ears. In Ear Piece (1998), for instance, she poses a series of questions about the nature of listening: Are you listening now? Do you remember the last sound you heard before this question? Are you listening to sounds now or just hearing them?

This kind of engaged listening, as composer Hildegard Westerkamp notes, is inseparable from acoustic ecology: "Conscious listening and conscious awareness of our role as sound-makers is an inseparable part of acoustic ecology, as it deepens our understanding of relationships between living beings and the soundscape" (Organised Sound, 2002, p. 52). Similarly, Jean-François Augoyard and Henry Torgue Augoyard urge us: "Let us listen to our cities!"—to hear the urban environment as an instrumentarium (Sonic Experience: A Guide to Everyday Sounds, 2005, p.4).

With these ideas in mind, I opened my ears to the chaotic symphony of Rumeli Hisarı: ships, ferries, motorcycles, cars, buses, pedestrians, simit sellers, seagulls, waves, airplanes, and more. Then, having immersed myself in this dense sonic landscape, I turned to enter the museum.

Doug Aitken, Ascending Staircase, 2024.

Installation view; © Doug Aitken, Courtesy of the artist; Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, Istanbul. Photo: Hadiye Cangökçe .

Stepping inside, the sudden quiet shifted my attention—from listening to seeing. Immediately, my eyes were drawn upward to Ascending Staircase (2024), with the fractured images reflected on mirrored surfaces in constant motion. Now, my eyes engage in a visual form of deep listening—catching glimpses of museum-goers, birds outside, the museum shop inverted, the staircase refracted like an Escher drawing. Where the sounds from different planes and pathways had converged in my ears, here they meet in my eyes. If Augoyard and Torgue urged us to 'listen to our cities,' here the museum prompts us to 'see' in the same layered way. While the urban soundscape unfolds outside—cars, buses, motorcycles, ferry boats, and the rhythms of pedestrians—the museum offers a silent counterpoint, a space of introspection. Yet Ascending Staircase disrupts this silence, presenting a fragmented yet interconnected sensory field. The visual enacts what we hear in our daily lives: layers of sound and movement, constantly shifting perspectives. Just as the soundscape inherently links us to our surroundings, this kaleidoscopic image-world reveals the hidden interconnections in our visual field.

This interplay of layered perception—acoustic and visual—finds parallels in music as well. For example Natasha Barrett's electroacoustic/musique concrète album Reconfiguring the Landscape (2023) captures the fusing of myriad inputs while maintaining her artistic flow. For a more vintage feel, Luc Ferrari's Petit Symphonie intuitive pour un paysage de printemps (1977). Both composers worked with both real world and studio-manipulated sounds in combination to enhance the sense of space in their audio. Ferrari was admittedly a visually-inspired composer, whereas Barrett made use of effects such as montage to reinforce a unique perspective of real or imagined space in each of her works.

Sonic Echoes in Visual Form

Doug Aitken’s work invites us to consider the interplay between movement and stillness, not only visually but also through sound. For myself, this is particularly evident in two of his works: 3 Modern Figures (don't forget to breathe)(2018) and Flags and Debris (2021).

In 3 Modern Figures (don't forget to breathe) three resin humanoid figures glow from within, shifting in color and intensity. They are posed as though absorbed in mobile devices—but the devices are absent. Instead, the figures are connected through rhythmic use of light, at times synchronized and pulsating, at other times independently shifting, swelling and flowing. Sound is central here: Aitken’s original composition unfolds fluidly, shaping our perception of time and presence. It is not merely an accompaniment; it shapes our perception of these figures, ebbing and flowing in a way that makes their presence feel both intimate and distant.

The slow unfolding of sonic material stretches perception across a meditative arc, much like La Monte Young’s Trio for Strings (1958) or John Luther Adams’ Become Desert (2019), with its interplay of long tones passed across a symphony orchestra interspersed with articulations of bells and chimes. The figures are simultaneously still and in flux, visually silent yet vibrating with rhythm. In all honesty, I forget about their missing phones and find meaning in the rhythmic dialogue between light and sound—connected yet disjunct, overlapping yet unaware. Though physically still, they are animated by the interplay of sound and light. They exist in a shared ecology, yet whether they will become aware of one another remains uncertain.

Where 3 Modern Figures (don't forget to breathe) explores isolation through stillness, Flags and Debris expands the interplay of sound and movement into the cinematic. Aitken’s film depicts a dreamlike urban landscape, where the everyday transforms into the surreal. The soundtrack drifts between identifiable sources and abstract textures—passing traffic swelling into a drone, the bubbling of wetland sounds merging seamlessly with urban noise. Real and artificial elements dissolve into an altered version of the real world. Aitken has captured a distinctly urban pastoral, where the sonic environment is as much a subject as the visuals themselves.

The imagery and sound of pandemic-era Los Angeles in Flags and Debris resonated with my experience of Istanbul during lockdown—when the usual drone of traffic and industry gave way to quieter, more delicate sonic details. It was a time marked by an undercurrent of anxiety, yet it also revealed a new kind of sonic beauty. Sitting with Flags and Debris I was drawn to the expansive, drone-based works like Ellen Arkbro’s For Organ and Brass (2017) and Catherine Christer Hennix’s Waves of the Blue Sea (2019). Like Aitken’s work, their compositions blur the boundaries of time and perception, using immersive layering and gradual transformation to create a sound world that is both haunting and captivating.

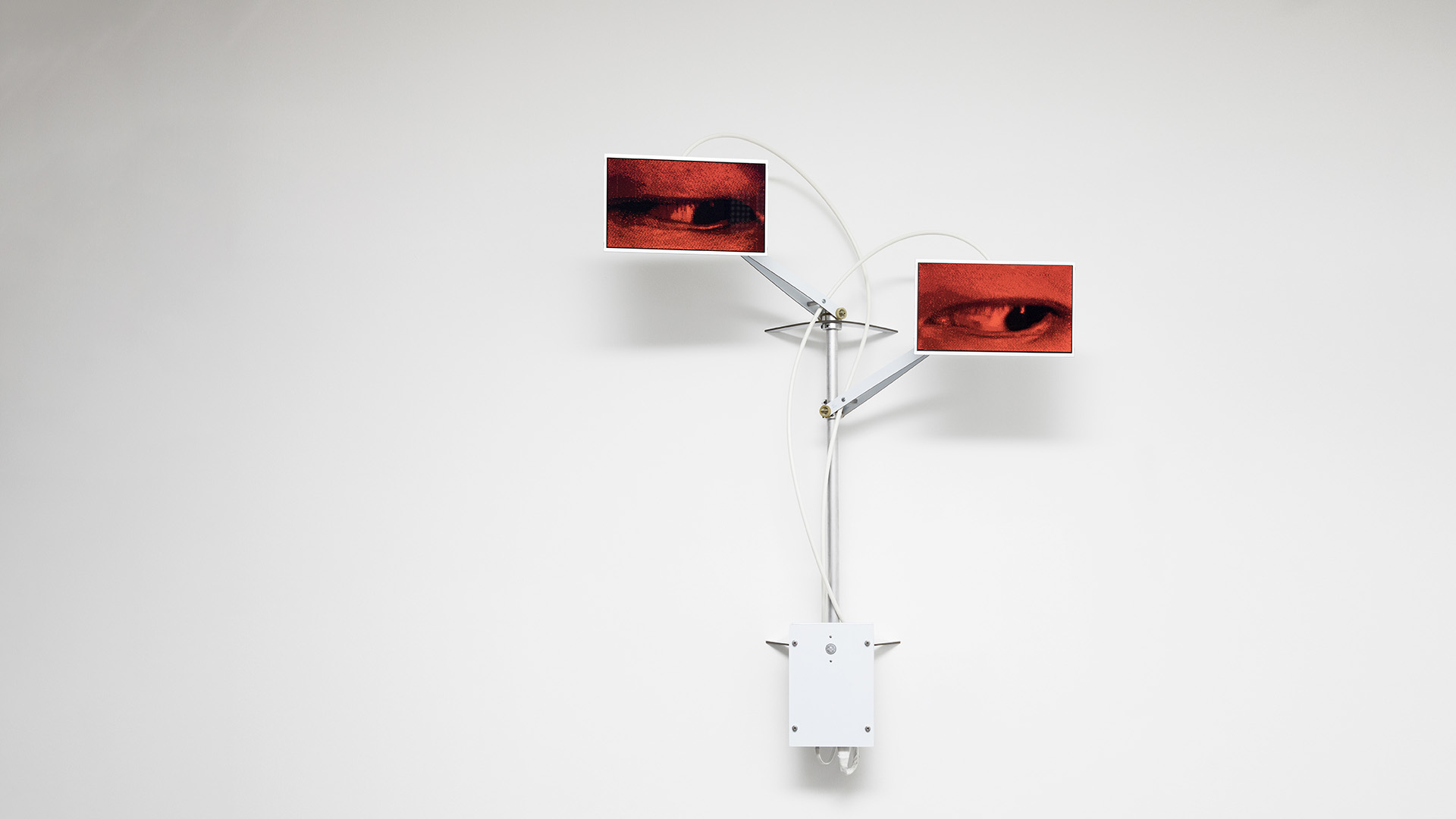

Doug Aitken, don’t think twice II, 2006.

Installation view; © Doug Aitken, Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, Istanbul. Photo: Hadiye Cangökçe.

Time, Cyclicality, Process-Based Minimalism

Cyclicality—both rhythmic and structural—permeates Aitken’s work. Nowhere is this more apparent than in don't think twice II (2006).

This piece, tucked away in a quiet corner, might seem unassuming compared to the large-scale works. Yet it pulses with a rhythmic intensity. Its concentric light patterns shrink and expand in sequence, evoking Steve Reich’s minimalist phasing compositions—such as Piano Phase (1967) or Drumming (1971)—where simple patterns shift in relation to one another, creating unexpected variations. Standing still before it, I felt transported into movement, as if time itself were expanding and contracting within the piece. Aitken himself states that he was listening to minimalist works by Riley and Reich while creating the piece, and the artwork is absolutely brimming with rhythm and choreography. The pulsing of light immediately brought to mind Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker's brilliant choreographyFase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich (1982) performed by the Rosas dance company. Likewise, Rosas danst Rosas (1983)—though without a musical score—relies on the rhythmic sounds of the dancers’ movements to generate its own percussive structure. (Both performances were featured at Fulya Sanat in 2011 as part of the sorely missed iDans festival.)

An image from the 2019 “DRUMMING” concert at the Borusan Music House, Istanbul.

Photo: Özge Balkan

Where don't think twice II (2006) captivated me with its steady pulse, sleepwalkers(2007) seduced my ears with vibrant shifts in tempo and texture—both audibly and visually. In this gallery version, mirrors within the exhibition space fracture and recombine these images, much like the rhythmic layering so present in Reich’s works. The editing style—alternating between micro and macro views, accelerating and slowing time—echoes musical forms that unfold through additive processes. I found myself thinking of Music for 18 Musicians (1974-76), or Terry Riley's In C (1964)where pulse and harmonic shifts create a slowly-evolving sonic landscape.

Doug Aitken, sleepwalkers, 2007.

Installation view; © Doug Aitken, Courtesy of the artist; 303 Gallery, New York; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich; Victoria Miro, London; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Hadiye Cangökçe.

For its first display at MoMA, sleepwalkers was projected onto the museum’s exterior, accompanied only by the ambient sounds of the city—allowing urban life to generate its own sonic counterpoint. For Borusan Contemporary, Aitken introduces a composed score, looping in parallel with the looping actions of the figures. The rhythmic interplay between image and sound is so seamlessly integrated that I cannot imagine them as separate. We, too, become part of the loop—mirrored, refracted, absorbed into the flow of time. The ear affirms what the eye perceives, drawing us into the rhythm of these five actors' daily lives.

Composition in Sound, Composition in Image

I came to this exhibition expecting to see visual works with sound as an accompaniment. Instead, I found myself listening intently. Aitken’s rhythmic structures and cyclical processes suggested sonic qualities even in the absence of sound.

So many of the concepts I typically experience through music—pattern, repetition, the expansion and contraction of time—became unexpectedly vivid through visual form. For me, composition has mainly been a sonic practice. Yet what I connected with most in Aitken’s work was his mastery of rhythm, time, and structure within the visual realm. Emerging from the exhibition into the instrumentarium of the Bosphorus, I find myself seeing rhythms and structures as much as hearing them. And I wonder: what is everyone else hearing?

ABOUT THE WRITER

Amy Salsgiver is an Istanbul-based American percussionist, composer, and educator who has

been an integral part of the vibrant local music scene for nearly two decades. Her creative work spans a broad spectrum of genres and disciplines — from classical to contemporary, traditional to experimental — often combining different aspects to powerful effect.

Her role as a performer keeps her at the heart of the contemporary and experimental music scene in Istanbul. As a contemporary percussionist she is actively working with composers and performing new music withHezarfen Ensemble, striving to bring new Turkish music to home and abroad. Her practice includes incorporating Turkish percussion instruments into unconventional contexts, reimagining their sonic possibilities. Amy is also the co-founder of sa.ne.na, a percussion collective dedicated to presenting influential works from the past fifty years to Turkish audiences. As an extension of this endeavor, she has collaborated with performers and composers such as Slagwerk Den Haag, Christian Benning, and Michael Gordon. Other percussion-based work includes performing with the Borusan Istanbul Philharmonic Orchestra (BIFO), studying the Ghanaian xylophone, the gyil, and appearing on stage and in recordings with jazz and pop music groups.

As a faculty member at Istanbul Technical University’s Centre for Advanced Studies in Music (MIAM), she leads both the MIAM Percussion Ensemble and the MIAM Improvisation Ensemble. Her courses encompass a broad range of subjects related to percussion, composition, and improvisation.

Amy is currently completing a PhD in music composition, focusing on improvisation and collaborative processes as vital tools in contemporary musical practice. She also leads an ongoing practice-based research project titled Sound Runs, in which she records the local sonic environment while running through it. These field recordings serve as both documentation and creative stimulus, inspiring works that invite audiences to engage more deeply with their surroundings.