Blog

Close Readings II -

Jim Dine: Two Hand-colored Colorado Robes

16 July 2020 Thu

This series of Close Readings emerged from a deficit I observed both in contemporary art criticism and in my own writing practice: Although exhibition criticism, interviews, and monographic artist texts are produced regularly, focusing on a single work, interpreting, and analyzing that one work is a form we encounter less often.

In the Close Readings Series, I focus on the works from the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection, one at a time, and aim to produce texts on the works that I am curious about and want to further elaborate on. My expectation from these texts is that they are new and experimental, bring a fresh perspective to the work rather than to adorn it, and take both me and the reader to places we have never been to before.

—Nergis Abıyeva

Jim Dine, Two Handcolored Colorado Robes, 1983.

95.9 × 149.9 cm, lithography.

Courtesy Cristea Roberts Gallery.

Looking into the garment’s historic development is interesting in this sense: “robe de chambre” is a form of leisure wear that emerged in 17th century France, influenced both by kimonos and the Banyan, to bring elegance and chicness to more daily aspects of life. Nicolas Bonnart made prints in 1667 and inscribed them as “homme en robe de chambre” featuring men in robe de chambres; the prints suggest that the robe de chamber not only appealed to aristocracy and the burgeoning bourgeoisie, but also to men of all social classes.

Jim Dine, Red Patch, 2005.

147 x 116 cm, lithography.

Photographed by Hadiye Cangökçe.

Jim Dine is an artist born in 1935 and is still alive and continues to create works. He has depicted robes many times since 1964 in different colors and mostly using screen printing and lithography techniques. It is no surprise, considering the repetition and reproduction of the image using mass production that Dine was an active artist of the Pop Art movement in the USA since the 1960s. Pop Art (incorrectly referred to as Neo-Dada), working with everyday, simple images in art. US-based Pop Art artists presented images seen on billboards such as Campbell's canned soups and Brillo's detergents as art. At a time when the “artist's brush” began to lose its importance, Jim Dine used printing techniques alongside artists such as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Allan Kaprow. I should admit that although the artist is famous for his colorful hearts and Pi-nocchios, I do not find those works visually interesting. I am interested in robe paintings not only because he poses provocative questions about the issue of gender, but also because this image is chosen by one of Pop Art's practitioners. American Pop Art targeted everything related to "high art" as opposed to the abstract expressionist movement that emerged out of the thought of Greenberg 2 in the US and the associated elitism. So, from the 17th century onwards, I think that the image of a garment that has a class code to be circulated repeatedly by one of the Pop Art artists is an extremely self-conscious choice rather than a “just because" choice.

Jim Dine, Yolk, 2001.

71 x 91 cm., Etching and aquatint.

Photographed by Hadiye Cangökçe.

Although Dine started to make these images with the effect of a robe advertisement he saw in the New York Times in 1964, the information I did not know when I began writing this article was something I found in an interview with Dine. For Dine, the image of the robe is also self-portrait. 3 What increases my interest is that Dine, after saying that this image is a self-portrait, also stated that he did not ever wear robes. In this case, we can think that the painting in question is either an imaginary self-portrait or a visual reflection of the artist's alter ego.

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait, 1500.

Courtesy Alte Pinakothek (Munich).

Dine's self-portrait is a self-portrait that challenges the image of the artist. This challenge is concealed in the historical adventure of the self-portrait: the individual artist in Western art began to show his authorship, which they started to gain slowly in the Middle Ages, by signing their paintings, and in the 15th century, the artist started to paint himself with the rise of Humanism and the Renaissance. Self-portrait, in a way, is a field of freedom for the artist, working outside a commission. Among the early self-portraits, the self-portrait of Albrecht Dürer, depicting himself as Jesus, is both an obvious example of the myth of the artist and one of the most daring. Although Dürer inscribed in his self-portrait at the age of 28, "I am Albrecht Dürer, I have illustrated my 28-year-old self," the painting has become synonymous with enough to be called "Self-Portrait as Jesus." Dürer's self-portrait of 1500, in many respects, resembles the portraits of Jesus: The portrait stands out by the frontal depiction. Usually, images of Jesus were depicted frontally. Another is Dürer's right hand and the gesture. Dürer's right hand is in the center of the composition, even though the hand is not giving a blessing. As if Dürer wanted to emphasize the creative hand of the painter, he painted himself like Jesus. Dürer's self-portrait undoubtedly produces a discourse that the individual is the creator rather than a manifestation of the creator.

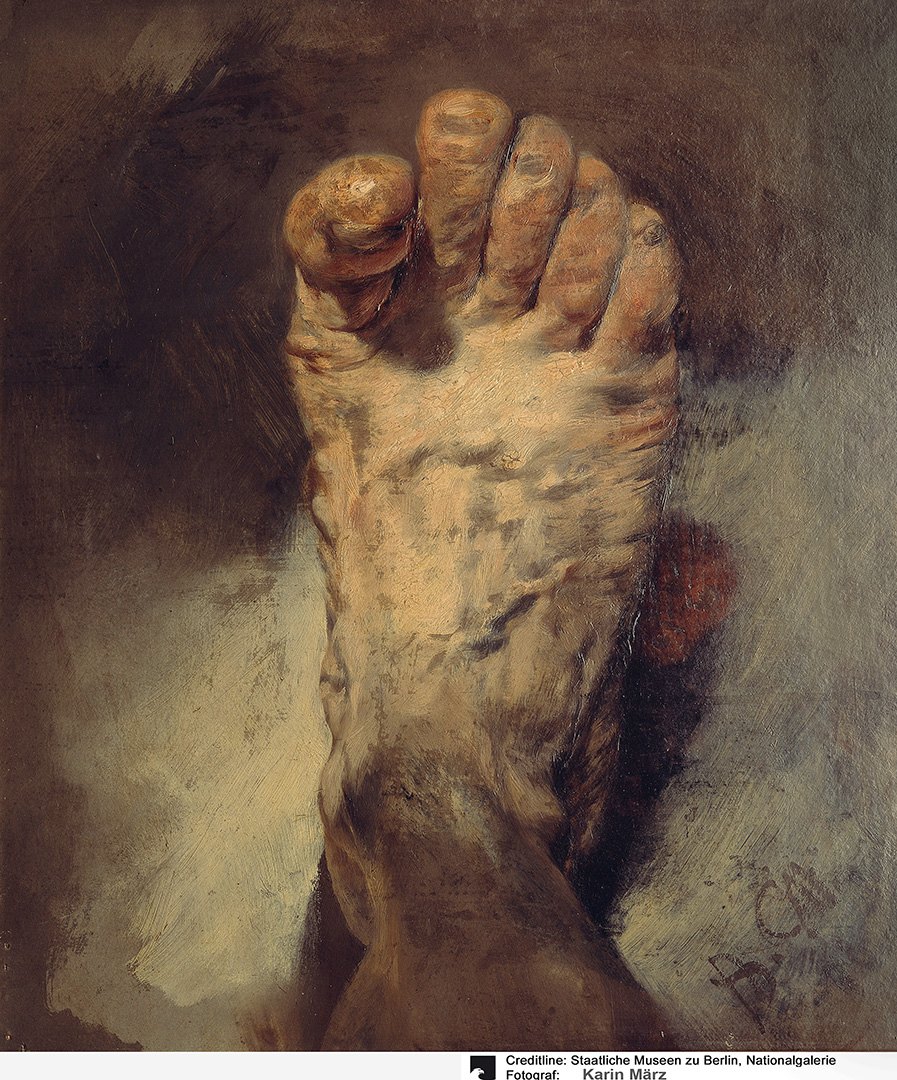

Adolph Menzel, The Foot of the Artist, 1876.

Courtesy Alte Nationalgalerie.

Since this very striking example of Dürer, who described artistic activity as divino artista 4, creating just like god, artists have painted their self-portraits in various ways over centuries. The individual artist showed themselves mostly with the materials that are the tools of their art such as canvas, brush, and palette. Although the history of art is filled with self-portraits that contain the image of the traditional artist, the invention of photography (1839) and the self-portrait type has also transformed over time since the mid-19th century. Thus, the extraordinary artist self-portraits, which gradually broke away from representation since the 19th century, took their place in the history of art: When Adolph Menzel painted his right foot in 1876, he perhaps had made a very avant-garde and extraordinary gesture.

Coming back to Dine's self-portrait, we see that this painting has a feature that the modern self-portrait usually contains: A resistance to the myth of the artist. This attitude of Dine, which refuses to play an artistic role, can be read as an extension of many avant-garde movements since the beginning of the 20th century. The fact that Dine depicts himself, leaving his face out, and with the robe which he has never worn, also brings to mind the definition of Darian Leader's art history: Leader had defined art history as the history of finding different ways to exclude things from an image 5 . I think that in the light of this definition, Din 's self-portrait, which he made by taking his face and body out of the image, turning himself into a trace, a gesture, shows a deviation in the self-portrait tradition and stands in a privileged place in the adventure of the modern self-portrait.

1 Instead of thinking by myself, I showed the images of Jim Dine’s robes included in the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection to my friends, who are writers, artists, and from outside of the arts. I asked them what the image showed. Although I received a few exceptional answers such as “a feminine man” or “a masculine woman”, most of the people I inquired with said that this image was a “man wearing a robe.”

2 Although Clement Greenberg does not make a direct reference to Pop Art in his works, in his article “Avant Garde and Kitsch”, the characteristics that he identifies as kitsch in opposition to the avant-garde are all tendencies and forms embodied by Pop Art. To read the article: http://sites.uci.edu/form/files/2015/01/Greenberg-Clement-Avant-Garde-and-Kitsch-copy.pdf , last accessed: May 9, 2020.

3 Ted Snell, “Here’s looking at: Jim Dine’s The mighty robe”, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/heres-looking-at-jim-dines-the-mighty-robe-80399, July 10, 2017.

4 Otto Kurz and Ernst Kris, Sanatçı İmgesinin Oluşumu: Efsane, Mit ve Büyü, İthaki Yayınları, p. 57

5 Darian Leader, Mona Lisa Kaçırıldı: Sanatın Bizden Gizledikleri, Ayrıntı Yayınları, p. 83

ABOUT THE WRITER

Nergis Abıyeva (1991) is an art historian, art critic and curator, based in Istanbul. Currently a PhD candidate at the Istanbul Technical University (İTÜ), Abıyeva graduated from Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University’s Art History department with the thesis “The Tracks of Dadaism on Surrealism” on the honor roll. During her undergratude studies, Abıyeva studied at the Brera Academy. She then graduated from the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University’s MA Program in Western and Contemporary Art with the master thesis, "The Art and Life of Tiraje Dikmen”. She won a Research Grant from SALT (İstanbul) with her research Tiraje Dikmen’s life and art in the context of Turkish artists who went to Paris in the 1950s. Abıyeva worked at Maçka Sanat Galerisi between 2015 and 2017 as an archivist for the 40th Year projects and contributed to the organization of the archive exhibitions. She is the assistant editor of the book, Görünmeyene Bakmak. Between 2017 and 2019, she worked at a private collection based out of Istanbul. Between April 2019-December 2020, she worked as a researcher at ARTER.

Her articles have appeared from 2015 onwards in periodicals including Sanat Dünyamız, Varlık, PRŌTOCOLLUM, Genç Sanat Dergisi, Istanbul Art News, Birikim and Argonotlar. She has curated the exhibitions, Kendiliğinden/Per se (Bilsart, 2020); Marvelous correspondences, subtle resemblences (Mixer, 2021). A member of AICA (International Association of Art Critics) Turkey since 2017, Abıyeva has been facilitating seminar programs and independent courses on modern and contemporary art since 2019.