Blog

A Master of Video Art is at Borusan Contemporary - Bill Viola: Impermanence

30 September 2019 Mon

Video art has its roots in the 1960s and has a history that we can define and analyze. In reality, during its early phases of technological development, video was not seen as an artistic discipline, at least until the beginning of the 1970s.

FIRAT ARAPOĞLU

firat.arapoglu@gmail.com

Early images were not very impressive nor were the sounds. Analogue video would lose its color as it was edited and copied: the recordings would be altered with each intervention and when videos were shown on different machines, consistency could not be sustained in the images. However, despite all these factors, the most important feature of video was its ability to be repeated. As major changes were taking place in the 1970s both in form and content, young generation video artists at the time were gaining their place in the spotlight as technological advancements were made and one of these names was Bill Viola. Viola interrogates complicated cognitive processes in his works through images and sound; by placing portraiture at the center of his practice, Viola consistently focused on portraiture, studying individual and social emotional states in his works.

Bill Viola’s work is exhibited at Borusan Contemporary between September 14, 2019–September 13, 2020, curated by Kathleen Forde. As this is the first time Viola’s work is featured so extensively in Turkey, I think it would be useful to look closely at both Viola’s works that are included in the exhibition and to look at his position in art history. Bill Viola’s interest in video art began as he was studying electronic media at the Syracuse University in 1969. The artist experimented with the many tools available at the university’s studios and while he continued studying painting, he was set to choose his ultimate tool of production. As Viola became increasingly active in the field of video, he created works that questioned states of humanity rather than the high-tech nature of this new mode of production. In an interview, the artist points out: “The real interrogation is that of questioning life and self; the medium is only a tool in this process.” This declaration reveals Viola’s painterly and emotional tendencies in his approach to art.

Bill Viola, Chott el-Djerid (A Portrait in Light and Heat), 1979.

© Bill Viola Stüdyo izniyle.

The exhibition features a selection of works, ranging from the 1970s to today. “Chott el-Djerid-A Portrait in Light and Heat” (1979) is an early work that provokes the viewers to contemplate on visual perception and illusion. The work’s title is derived from the eponymous salt lake on the Saharan Desert in Tunisia and problematizes the state of seeing mirages due to the desert heat. The work was filmed in Tunisia, Illinois, and Saskatchewan, visualizing the disorientation in different climactic conditions and a certain ominousness. This early work looks closely at the perception of reality through using hallucination as a tool and drawing on the tension between the physical and the psychological.

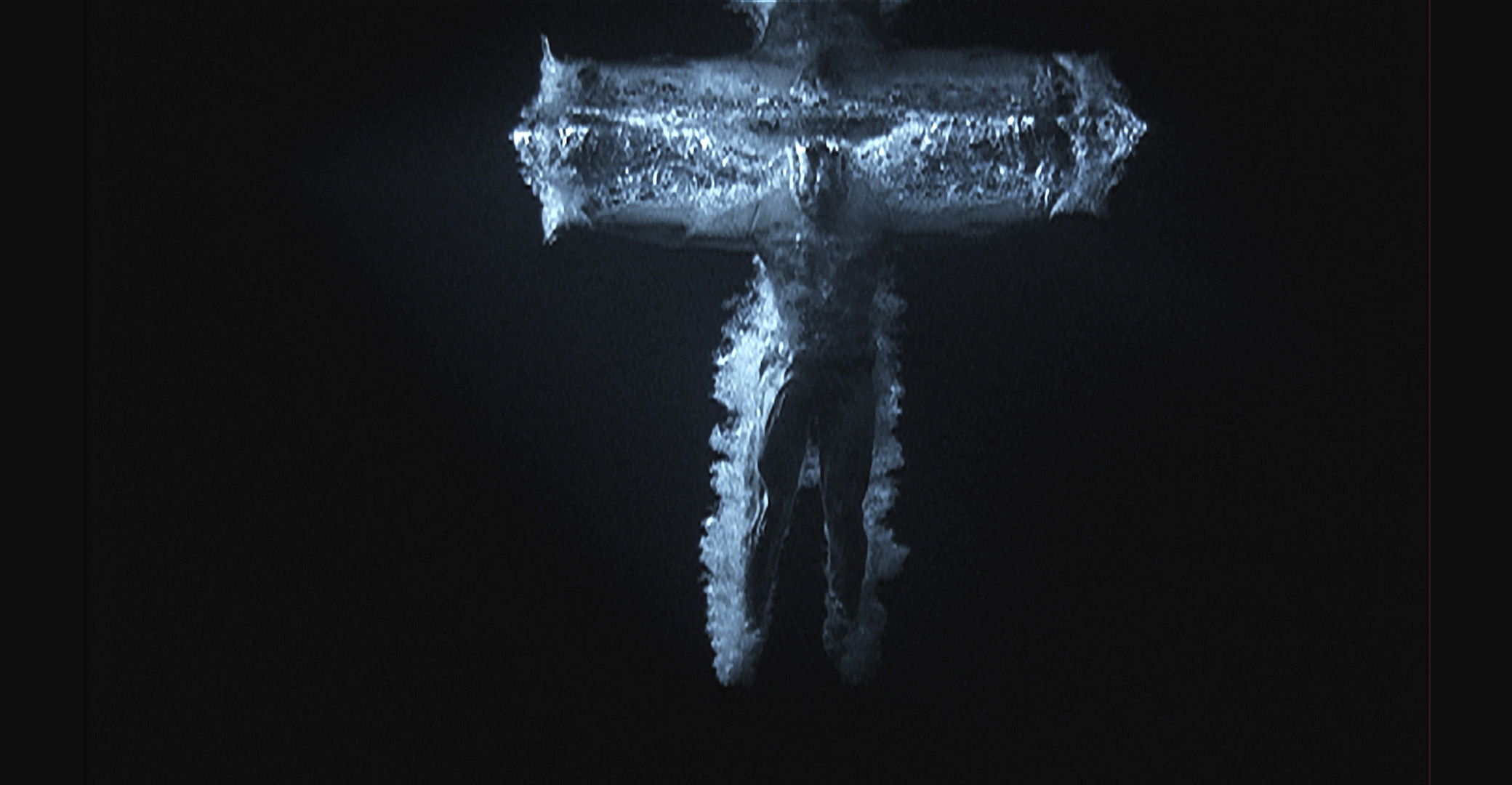

With “Ascension” from the early 2000s, an image of a man falling into the water with his clothes on, the disruption of the serene landscape and the slow-motion capturing of the sinking into the water are captured. The figure moves slowly and gets suspended on the water’s surface, entering the serene landscape and then disappearing into the depths. The body that is included into the landscape at the beginning of the shoot is returned to its old state as the body exits the image. The circle of life, which is one of the themes in Viola’s work, keeps coming back throughout the exhibition.

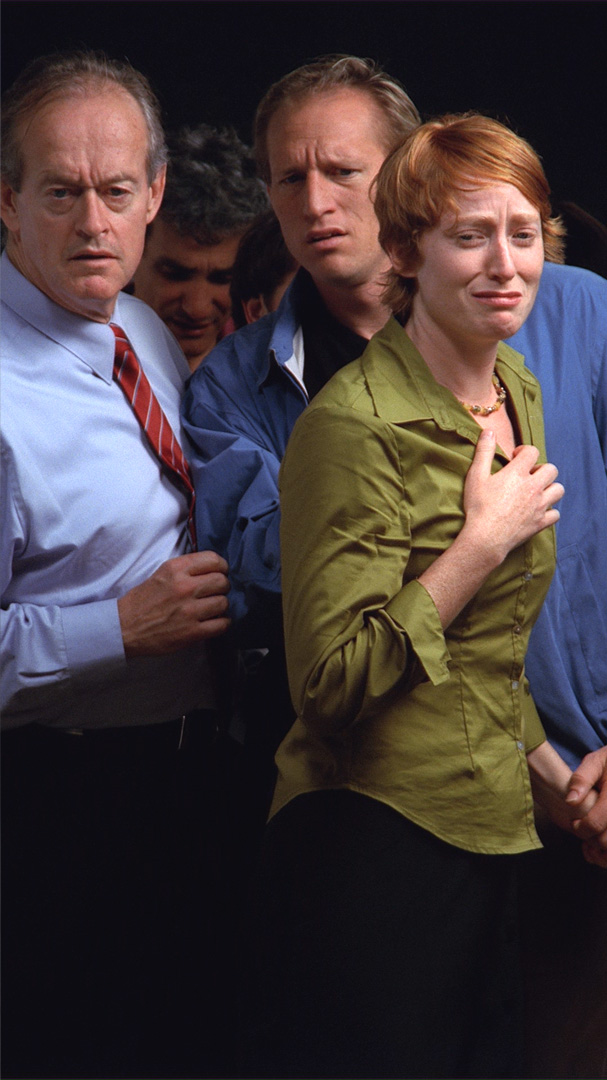

The work “Observance” shows a group of figures looking at the viewer directly; the gazes are fixed to the lower right corner of the frame. The work is constructed outside of the reflex of the usual portrait tradition, because usually in portraits, the figure’s gaze is often projected from the front or from ¾ position but most often from above. In this video, Viola skillfully monumentalizes pain, not sacredness, in a performative transition by using figures staring at the lower right. Another crowded composition “Tempest (Study for the Raft)” (2005) shows the exposure of nineteen men and women of different origins to high-pressure water. In this process, some of the figures fall to the ground, some of them stand firm and others support each other. “Reminiscent of Noah's Flood, the video visualizes the most fundamental solidarity of humanity as a social entity.

In the late 2000s, “Three Women”, part of the Transfigurations series, questions the time and processes that transform the inner life of the individual. Sufi Ibn al-Arabi's ”life is an endless journey” is taken as a departure point for the video. A mother and two daughters quietly emerge from a dark space and once they pass through what could be considered a time tunnel, they gain color, which could be interpreted to symbolize gaining life. After a short time, the mother states that she will return to the dark and draws her children to this area once again. This time the story of Hades and Persephone comes to mind. In the “Ancestors” video (2012), we encounter the tradition of dual portraits. The mother and her son, who became crystal clear after being blurred, performed a difficult walk across the desert. Stability and solidarity are phenomena within the landscape that reach our consciousness.

Another double portrait, “Encounter” (2012), is based on the lives of two women. Two women, one young and the other older, set out on different paths, continue their journey after a brief encounter. Time and space-extrapolation are again among the phenomena encountered in this video. In the “liquid” videos, “Madison” shows a young woman underwater and “Sharon” shows another young woman in the same way (2013). Finally, the “Trial” (2015) shows the presence of a young woman and a man appearing on two vertical screens in red, black and white fluids. These fluids again refer to the cycle of life through the references to blood, soil, and water.

As Kathleen Forde also articulates in her text, Viola’s works deal with issues including birth, death, fear, and reality. The slowness of the sequences in his works, the mysterious environments that the figures are in strengthen the visual language of the stories. Seeing the ambivalence of perception as well as the games that people play so clearly in the exhibition will be an important experience. Sensorial experiences, the ambiguity of time—time speeding up or speeding down—, the relativity of the identifications of the past and future are among the key words for the exhibition. Forde reminds viewers of the near-drowning experience that Viola had as a child and provides us with a clue to the artist’s relationship with “water”—the artist had almost drowned at the age of six. Forde recommends us to interpret this anecdote not as autobiographical, but as an experience. Furthermore, the artist’s video “Surrender” from 2001 is a very strong expression of this notion. As is clear in almost all of Viola’s works, a very familiar notion that relates to the state of being human by intensely delving into the very essence of that notion.

The artist's interest in Zen Buddhism, Christian and Islamic Sufism can be seen, for example, in the use of moving video with very slow movements. For example, in the “Emergence” video (2002) commissioned by the Getty Museum to be included in the exhibition “Bill Viola: The Passions” (2003), Christian iconography, inspired by Masolino da Panicale’s “Pietà” showing Mary embracing Christ as he is taken down from the cross, was used. But, in iconographic terms, the same video is reminiscent of the “Resurrection” scene, which works with the revival of Jesus. This once again shows that Viola skillfully gives birth to the tension by working with both birth and death. Metaphysics includes important data to help understand the artist and his work. And of course, one should not forget that the artist scrutinizes the main existential and emotional practices of human beings, including birth, death, and solidarity.

Since the 1990s, video artists had been embraced by museums and galleries. As the concept of the Internet and new media became widespread, video art now had a past that could be historically periodic. In this way, as art history often does, some artists have been chosen as ”masters of video art”. These names include Nam June Paik, Bill Viola, Gary Hill, Tony Oursler. Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci and Paul McCarthy are also included in this group, especially through early work based on performance documentation. Bill Viola's “Impermanent” exhibition gives the audience a chance to witness a cross-section of the history of video art with examples of the artist's work, which has now become cultural and artistic assets in the context of numerous institutions and collections.

This article has been published in Turkish as part of the special September issue of Istanbul Art News.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Fırat Arapoğlu is an art historian (PhD)/art critic & independent curator. He lives and works in İstanbul. He has been working in Economic, Administrative and Social Sciences Faculty, Department of Social Sciences, Altinbas University as an Assistant Professor. He curated numerous exhibitions in Turkey and abroad, most recently including: “Future Unforgettable”, Krassimir Terziev solo show (2019, Versus Art Projects, İstanbul), The Fifth Agreement, Esra Satiroglu solo show (2019, Summart, İstanbul), and “Simbart One-Day” solo show programmes. He co-curated 3rd International Canakkale Biennale and 3rd and 4th International Mardin Biennales. He has written articles in national and international art magazines such as Genç Sanat, Art-İst Modern & Actual, ICE, ARTAM, Art Unlimited, Critical Culture, RH+, İstanbul Art News and Flash Art. He has also written articles in national newspapers called Birgün, Cumhuriyet and SOL. He has also written national and international symposium proceedings about art and art education and has been giving lectures in İstanbul Modern Art Museum, Moda Sahnesi, Narmanli Sanat, İstanbul Bilgi University. He is the 2018-2020 President of AICA- Turkey (International Association of Art Critics-Turkey).